William Golden’s Militia Service – South Carolina Revolutionary War

Former Virginian and Colonel of South Carolina Militia Philemon Waters was given the mission in 1781 to ‘recruit’ to support the revolutionary militia. This included recruiting loyalists to switch sides.

Colonel Waters had a reputation of treating, and being treated by, local loyalists with respect and fair brokering of relations.

Among those recruited was a Will(iam) Goulding, aka William Golden, from the Newberry area. Colonel Waters had his own plantation in the Newberry area, just off of Bush Creek (Bush River). William’s father Thomas Golden lived just off of Matthews Branch of Bush Creek.

Who was William Goulding?

This is a relatively simple question to answer. There was only one living in the region to choose from: William Golden, c1750-1809, of Beaverdam Creek, off of the Saluda River on the Newberry side. William’s father Thomas Golden lived just off of Matthew’s branch of Bush Creek in Newberry not far from Colonel Philemon Waters plantation.

There was an elderly William Golding, c1705-1782, that lived nearby in Abbeville. He and his son Anthony Foster Golding, 1746-1801, are recognized by the DAR for their service — driving a wagon to deliver food and stuff to the militia. Neither served nor claimed to serve in the militia. Anthony Foster Golding had a son William, born just as the Revolution (1767) was starting.

Not too far away in Wilkes now Lincoln County (1796), Georgia, there was a William (Allen) Golden, Jr, c1750-1810, married to Elizabeth Ellender, 1737-1778. This would have been out of area for Colonel Waters‘ recruiting efforts, which were focused on the Newberry area, South Carolina.

Acknowledgement: Identification of William Goulding as William Golden, son of Thomas Golden, both of whom lived off of Beaverdam Creek, near Matthews Branch, off the larger Bush Creek is all circumstantial identification based upon time and place. There are however, no stray William Golden / Goldin / Golding or Goulding known to have been living in the region.

A Wise Choice for Outreach to Loyalists

Colonel Waters was a wealthy plantation owner from Virginia that lived in the midst of South Carolina’s densest concentration of fervent loyalists anywhere in South Carolina. This was the Dutch Fork and Newberry, South Carolina area.

Waters and his plantation escaped the ravages of war. On being ‘fair’, Waters appeared to recognize the war for what it was: mostly a civil war — a most uncivil one by some on both sides.

Colonel Waters once put himself between a senior militia officer and a captured loyalist that was considering switching sides. Blind with rage and any attempt to make a deal, the revolutionary general was going to shoot the loyalist — Colonel Waters stepped in between and said that the general would have to shoot him first. Everyone walked away alive.

Philemon Waters was somewhat successful at recruiting former loyalists … and could have done better if locals believed that South Carolina would eventually pay them … which Waters himself doubted.

Recruiting Bonus – Sign Up and Get a Slave!

Colonel Philemon Waters wrote to the South Carolina Senate with his plan to entice new enlistments (June 1781):

“… The Proclamation was a Negro to each Private that would enlist for Ten Months; the Circumstances of the times occasioned the Men to fear they never would get Paid, and to Satisfy them that there was not the least danger, I never required pay for myself; but sometime in the Month of July or August same year the Man Seemed much dissatisfied and Commotions seemed to arise in the Camps at a Place called Brown’s old field at Congarees, I used all the Influence in my Power to appease them, telling them they had proved themselves good Soldiers on some Occasions & hoped they would continue so to do & promised that if the Publick never paid them …”

Colonel Waters put his wealth to work and kept his promise to those he recruited by paying them out of his pocket.

After the war, Colonel Waters would seek compensation from both the South Carolina Senate and House … if they should feel kindly to provide something.

Sending the same letter to both the Senate and to the House, he wrote:

” … your Petitioner at his own expense Raised & equipped a Troop of Horse in General Sumter’s Brigade of Cavalry without putting the State to one farthing of Expense and at the Expiration of ten months the term of enlistment your Petitioner paid off the Troop to a man and as the Horses, Saddles, Bridles and other Furniture at that time was very dear it cost your Petitioner a considerable sum to equip the Troop as above, though your Petitioner made use of these articles in paying off his Troops still your Petitioner most Humbly Conceives, the Service of the Horses & wearage of the Equipment is a Claim your Petitioner is entitled to as none of those articles were lost belonging to the Troop, consequently the State had nothing to pay but what was promised for enlistment In which case your Petitioner humbly Conceives himself entitled to pay for the service of his Horses &c – whereupon your Petitioner rest his case entirely with the wisdom and Justice of this House to grant him such relief as they in their wisdom shall deem meet and your Petitioner as in duty bound will pray …”

S/ P. Waters

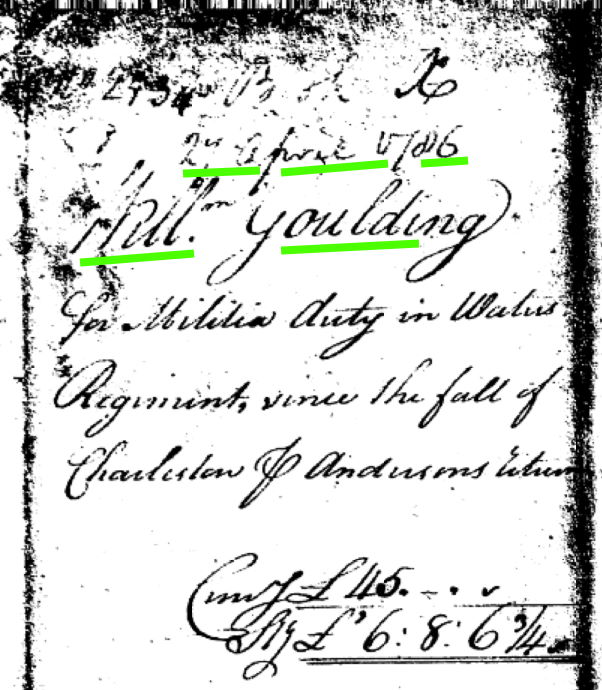

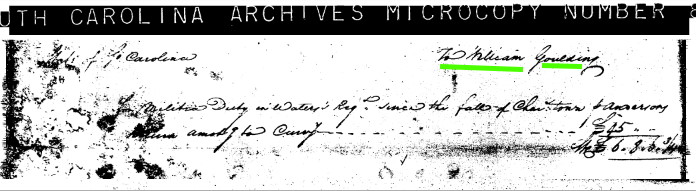

2 April 1786 — Militia Service Indent Filed in Charleston

An ‘Indent’ was the promissory note issued by South Carolina to pay for services or good rendered during the Revolutionary War. Theoretically it could also be used to get a discount on land made available by the state.

William Golden‘s (Goulding) time of service is not clarified in his ‘Indent’, only that it occurred ‘after the fall of Charleston (after May 1780) and associates his service with (General Thomas) Sumter‘s Brigade, and indirectly with (Colonel) Robert Anderson as a witness of his service.

Sumter had been active since the war’s beginning so this does not provide an exact date of William’s service. Sumter had spent much of 1780 recovering from wounds and returned to military service in early 1781.

The association with Colonel Robert Anderson is unclear. One record in William Golden’s Indent document collection appears to say ‘Andersons (witness)‘ … the second word is mostly illegible but resembles ‘witness’ which make sense in that Anderson was a witness of William’s service.

—— It can be assumed that the period of service was 1781-1782. When Colonel Waters sought compensation for his recruiting efforts, Waters makes reference to having made his special offer of ‘a slave for 10 months of service’ having occurred just once.

Robert Anderson was a militia commander responsible largely for the defense of the Ninety Six District along the Savannah River, especially in the Augusta, Georgia area opposite of Edgefield, South Carolina.

Robert Anderson was a major plantation owner (2,100 acres) in the area. Anderson County, South Carolina is named after him today. He was promoted to General of Militia only after the war ended.

William Golden/Goulding‘s Indent was worth ‘Six Pounds, Eight Shillings and six pence’ or about $31 in purchasing power at that time.

— A farmer (agricultural laborer) could expect to earn approximately 48 cents per day in 1780, if in Massachusetts, 50 cents in Vermont. In Charleston, South Carolina, a laborer could expect to earn 50 cents per day.

Slaves easily sold for $250+ … Colonel Philemon Waters offer of a $250+ slave mattered when military service (if paid) would bring only a tenth of that.

— Technical Note: Slavery was not yet widely spread in this area of Carolina. The Bush River region (Newberry, South Carolina) had a very large Quaker population — strongly anti-slavery. Most people were simple farmers. Certainly they could not afford to save and to buy a slave on their own. Slave prices kept significantly rising in the years after the war, tripling by 1800. For some: getting a slave in exchange for militia service was no doubt a major incentive.

Yet, slavery was also unpopular in this region. Many would migrate out of the region and move to non-slave areas, predominantly to Ohio. By 1810, there was a significant depopulation of the region.

Prior Loyalist Militia Service, 1777-1780

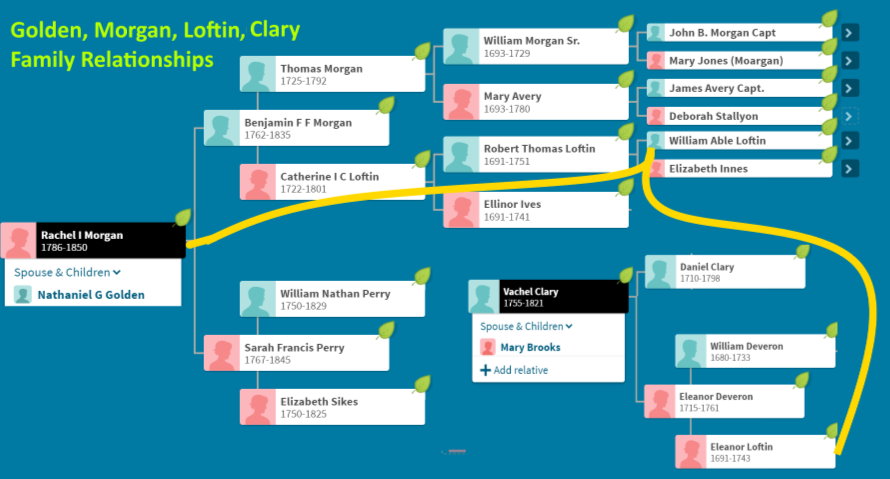

The William Golden family of Newberry, South Carolina was closely associated with other loyalist families. Pay records indicate that William served in loyalist militia from approximately 1777-1780 within the Royalist Regiment commanded by Major Vachel Clary.

— Good and Bad. Vicious vs respectful. Bloody Bill Cunningham is always taught in the history books to scare and to instill dislike of loyalists. The anti-thesis of Cunningham was Vachel Clary, the loyalist commander at Newberry under whom William Golden served. Vachel was well liked, was not hateful, spiteful and vengeful in his dealings while at war. Clary was not a Cunningham, nor were his troops.

A daughter of William Golden (c1750-1809), Margaret Frances Golden (1784-1875) would also marry into the strong loyalist family of Daniel Cotney (1745-1781) when she married his son William Cotney (1773-1819).

Goldens and Vachels were cousins, sharing Loftin and Innes grandparents.

In the chart below: South Carolina’s Upper Country and the Ninety Six District were full of new arrivals and transplants. How our Golden family connected with other kin, many of whom were loyalists before they supported the revolutionary cause — and many or most being from Virginia or Maryland. The Morgan line were from Connecticut.

William Golden‘s first-born son was named Nathaniel Greene Golden (1783), perhaps to show where his sympathies were. General Nathanael Greene was the commander of Revolutionary Forces in South Carolina at this time, and General Greene had turned the war against the British.

Got info? Bill Golden [email protected]

Comments, Questions and Thoughts

You can reach Bill Golden at [email protected]

GoldenGenealogy.com is moderated by Bill Golden — in search of his own family.

To find his, he collects and shares what he finds. His Pokemon strategy is to collect them all while finding his.

Bill Golden [email protected]